Madonna Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim

— Jean Fouquet, 1452

This intriguing late-medieval masterpiece is the absolute highlight of the KMSKA’s collection. The French court painter Jean Fouquet created this apparent modern painting in the middle of the 15th century. Fouquet presents the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven. The three blue cherubim represent purity and air, the six red seraphim love and fire. The unusual, intense use of color and bold representation make the painting fascinating.

.

The Intrigue

— James Ensor, 1890

The Intrigue is one of the finest masquerades in James Ensor’s entire oeuvre. Masks customarily hide the true face of their wearers. In Ensor, they function in precisely the opposite way. He used these disguises to reveal the inner malice of his characters in scenes that are bizarre and grotesque. Some art historians have interpreted this work as Ensor’s personal vision of marriage. The bride has captured the groom. There’s nowhere for the poor man to go. He used abrupt color transitions in this painting. The aggressive contrasts of unmixed colors are equally striking. Ensor allows light and color to blend into one another.

.

Flowers in a vase

— Jan Breughel II, 1620

Jan Breughel II was the first important painter to elevate the floral still life to a genre in its own right.

On a table against a dark background stands a terracotta vase with an impressive column of flowers. Two slender branches, on the one hand the poisonous imperial crown bending slightly to the left and on the other the white lily branch tending to the right, reach almost to the top edge of the panel. Below this, a multitude of flower types are arranged that have different stages of bloom and growth.

Brueghel painted directly in oil on wooden or copper panels during the bloom of the flowers without any preparatory drawings. He shows himself to be a virtuoso in the field of flower painting through his technical perfection, his sense of harmony and his sense of composition.

.

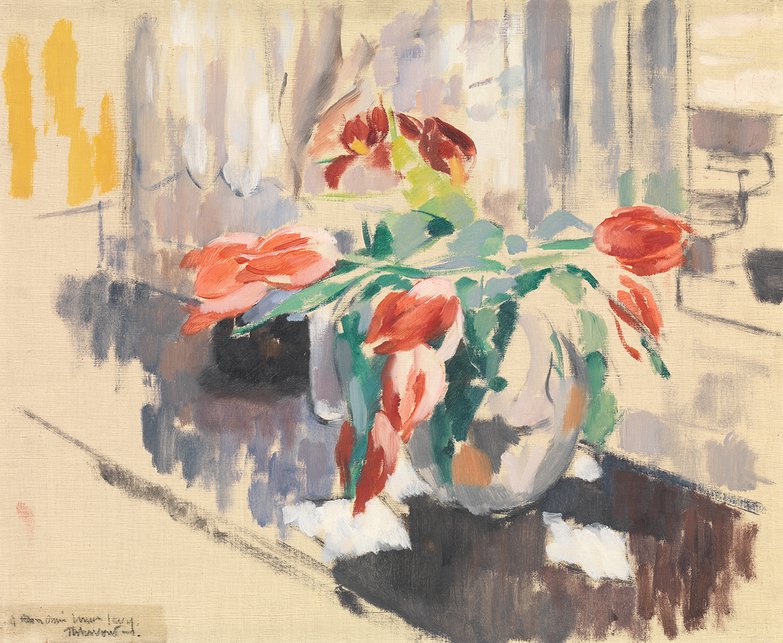

Tulips

— Rik Wouters, 1912

When Rik Wouters talked about paintings, it was almost always just about the color. When he began a new painting he started with the subject in a few broad outlines supplemented by the color patches that would determine the final result. That this painting is also about color, goes without saying.

.